A Valentine’s Day in University Park, 1932

A Candlelight Dinner and a Heavy Heart

Randolph Dawkins set the table with care. Two plates, a flickering candle, and the best he could manage on a labor man’s wages in their quarters without electricity or running water. His wife, Armenda, smiled as she sat down, grateful for the quiet moment away from the estate’s demands. For a while, they ate in silence, savoring the rare peace.

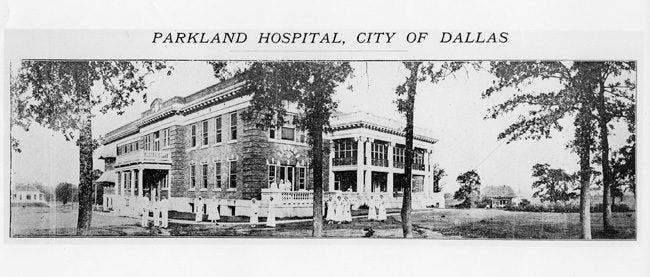

Then Randolph spoke, his voice low. “I stopped by Parkland today,” he said, eyes fixed on the flame. “To see Uncle Will.”

Armenda’s fork paused mid-air. “How is he?”

Randolph shook his head slowly. “Not good. They’ve got him in isolation now. You should’ve seen the precautions! They don’t let you near a man with this sickness without a mask. Just a strip of gauze tied across my mouth, but it’s something. I kept my distance, didn’t touch a thing. The nurse cracked the window wide open so the air could move. They say that’s the only way to keep the germs from hanging in the room.”

He pushed his plate away, hands trembling slightly. “I washed my hands till they burned before I left. Didn’t dare take a sip of water while I was there. Everything he touched, everything in that room… it’s dangerous. This disease! It floats in the air when he coughs. You breathe it in, and it settles deep in your lungs. That’s how it starts.”

Armenda reached for his hand, her eyes wide with worry. Randolph squeezed back gently. “I had to see him,” he whispered. “But Lord, I pray I didn’t bring anything home.”

He leaned back, staring at the candle as if it held answers. “They say it’s a slow march. It started with pneumonia last summer, then toxemia and his pleural effusion on New Year’s Day. Since then, nothing but downhill. I feel so helpless, Armenda. He was more of a father to me than my own daddy. We all came here from Paris thinking Dallas was our bright future. Now…” His voice cracked. “Now I’m watching him slip away.”

The Call

Two days later, Valentine’s warmth had faded into a gray February morning. Randolph clocked in at the Sears building on Lamar Street. It was a sprawling 1.5 million square foot monument to commerce just South of Downtown Dallas. He was barely settled when his boss approached. “Phone call for you,” the man said, his tone clipped.

Randolph’s stomach tightened. He walked the long corridors slowly, dread pressing down with every step. At the switchboard, he lifted the receiver, his voice barely a whisper. “This is Randolph.”

The words that followed shattered him. A Parkland orderly delivered the news in a single, merciless sentence: Will was gone.

Randolph fell to his knees, sobbing, the sound swallowed by the hum of machinery and footsteps. His world had collapsed, but there was no time for grief. Jobs were scarce, and his straw boss wasn’t known for mercy. He wiped his face, stood up, and finished his shift hollowed out by loss.

That night, he walked to his uncle’s home at 1819 Lincoln Street to gather what little remained before it was discarded. Among the belongings, he found a photograph of the two of them at a church barbecue back in Paris, TX. It was a moment of joy frozen in time. He tucked it into his coat and began the long walk back to the prestigious address of 3736 Stanford Avenue, in University Park, more than an hour on foot. When he arrived, he didn’t walk through the front door, but through the alley and into the servants’ quarters.

Dallas was tightly segregated at this time, and he would never be allowed to enter through the front door of this home. That was for the white white people. Instead, he was tucked into the servants’ quarters buried deep behind a grand estate. His wife, Armenda, was a domestic for the family that owned the property. Their apartment didn’t have running water or electricity. It wasn’t much, but it was theirs, and in the depths of the Depression, that counted for something.

Exhausted and late for dinner Randolph finally came through the door. Armenda saw the bundle in his arms and instantly knew what happened. She rushed to him, and as he tried to explain, he pulled out the photo and dissolved into tears.

The Burial

Will Dawkins had been the first in their family born free. His life deserved dignity. But dignity was hard to come by in 1932. Plans for Mount Auburn Cemetery fell through. Forest Lawn was considered, then abandoned. In the end, there was no choice but the pauper’s cemetery. Most were buried there the same day they died. Will waited three days, a measure of the family’s anguish and torture at not being able to provide funds for his burial.

On February 16, Randolph and Armenda traveled far north of town to lay him to rest. The place was called Letot, TX. The City & County of Dallas had banded together to purchase this new tract of land that would house their needs for decades to come. Randolph remarked to the grave digger, “I thought this was a cemetery.” To which the reply came, “It is now.” Will was the very first burial at Dallas City Cemetery.

The land was pristine, acres of open country. Standing at the edge of the grave, Randolph clutched the photograph in his coat pocket, the last tangible piece of a man who had shaped his life. The wind swept across the fields, carrying with it the silence of things left unsaid.

This wasn’t the ending they dreamed of when they left Paris, TX for Dallas. But in that moment, with Armenda’s hand in his, Randolph vowed to keep Will’s memory alive. Because even in the shadow of despair, love endures.

Will Dawkins was born in 1888 to a freedman named Nathan who was just 12 at the time the Civil War ended. The parents fled the plantations of South Carolina and brought Samuel (15), Nathan (12) and, Roda (8) to Paris, TX to start a new life. There they gave birth to at least 5 more children: Harriett, Sanford, Rachel, Clarksville & Lewis. It was in Paris that they were finally able to legally wed in 1873.

Note: The houses on Lincoln and Stanford no longer stand.