Today marks a turning point! Not just for a forgotten cemetery in Northwest Dallas, but for the 2,054 people who were laid to rest there without the dignity of a lasting marker. After years of research, advocacy, and quiet persistence, the City of Dallas has released $90,000 to help fund the purchase of 1,000 new headstones for Dallas City Cemetery, also known as the Dallas Pauper’s Cemetery. They were matching the $50,000 of private donations already allocated to the effort.

A Personal Note

Today also happens to be my birthday, and I can’t imagine a better gift than this. After years of research, advocacy, and quiet determination, to receive the funding that will finally give 1,000 people their names back feels like the most meaningful birthday present I could ever receive. It’s a reminder that history isn’t just something we study; it’s something we can change.

As soon as the funds clear my bank, they will be transferred directly to Calvary Hill Cemetery, fulfilling the contract I signed on September 30, 2025. On that same day, I will deliver the list of the 1,000 individuals whose stories will finally be anchored to the ground where they rest.

And then the work begins.

While the markers are being created, I’ll be sharing regular stories about the cemetery’s permanent residents — the people whose lives, struggles, and final days shaped the early 20th‑century city we inherited. They deserve to be known. They deserve to be remembered.

A Cemetery That Tells the Story of a City

They say there are a million stories in the naked city. Dallas City Cemetery is no exception. In fact, it may be one of the most concentrated archives of human experience in the entire county.

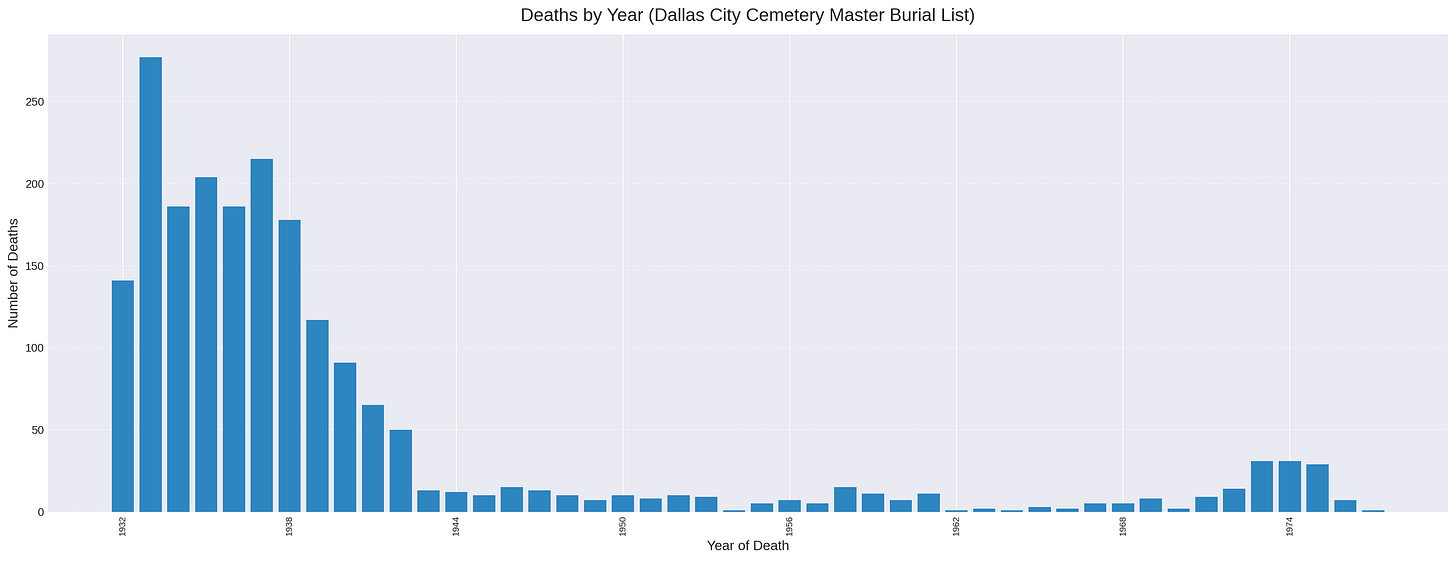

A staggering 84% of all burials occurred in the cemetery’s first decade, from 1932 to 1942 — years defined by the Great Depression, widespread poverty, and the absence of modern medical care. As prenatal care progressed, antibiotics emerged, and tuberculosis treatments improved, the burial rate dropped sharply. The cemetery’s population is a demographic snapshot of a city in crisis, then in transition.

Most Common Places of Death

1,002 – Parkland Hospital/Woodlawn (including 278 stillborn)

177 – Bradford Memorial Hospital

116 – Hutchins Convalescent Home

75 – St. Paul

43 – Baylor Hospital

21 – Hope Cottage

These institutions cared for the city’s poorest, sickest, and most vulnerable residents, and their records form the backbone of this cemetery’s story.

Unnatural Deaths

Among the 2,054 burials, 171 were attributed to external or unnatural causes, a sobering reminder of the dangers of early‑20th‑century urban life.

Homicide: 24

Suicide: 18

Drowning: 8

Burns: 29

Poisoning: 16

Train/Railroad incidents: 19

Explicitly “Accidental”: 9

Stab/Knife wounds: 9

Hanging/Strangulation: 7

Exposure: 5

Gun-related (subset): 31

Each number represents a life cut short, often violently or tragically — and until now, often anonymously.

What Comes Next

The die is cast, but the story is still unfolding.

Over the coming months, as the markers are carved and prepared, I’ll be sharing the histories of the people who will soon have their names restored to the landscape. Some stories will be heartbreaking. Some will be surprising. Many will challenge assumptions about poverty, race, illness, and survival in Dallas during the hardest years of the 20th century.

But all of them will remind us why this work matters.

A cemetery is not just a place of burial. It is a record of a community’s values — and for too long, Dallas allowed this one to fade into obscurity. Today, with this funding, with these markers, and with this renewed commitment to remembrance, we take a step toward correcting that.

Alea iacta est.

The die is cast.

And the work of restoration — of memory, of dignity, of history — moves forward.

I am immensely humbled by this moment and I’m flipping back and forth between the gravity of what we are about to do and the joy of being able to finally roll up my sleeves and get to work!

Please subscribe to this blog so that we can enjoy this journey together!

Happy birthday! Love the article!